Dr. Maria Bajwa

September 26, 2023

As a healthcare simulation educator, I set out to explore how simulation-based education is understood, adopted, and practiced across various regions of Pakistan. This journey, both professional and deeply personal, allowed me to examine healthcare teaching methods through a culturally informed and globally trained lens—especially as someone who once called this country home.

Having lived abroad, I returned with a hybrid perspective: one that honored Pakistan’s cultural roots while also critically engaging with its healthcare and educational structures. This unique vantage point enabled me to observe how social subcultures across different regions shape healthcare education, particularly in the context of simulation—a pedagogical approach still relatively new in many parts of the country.

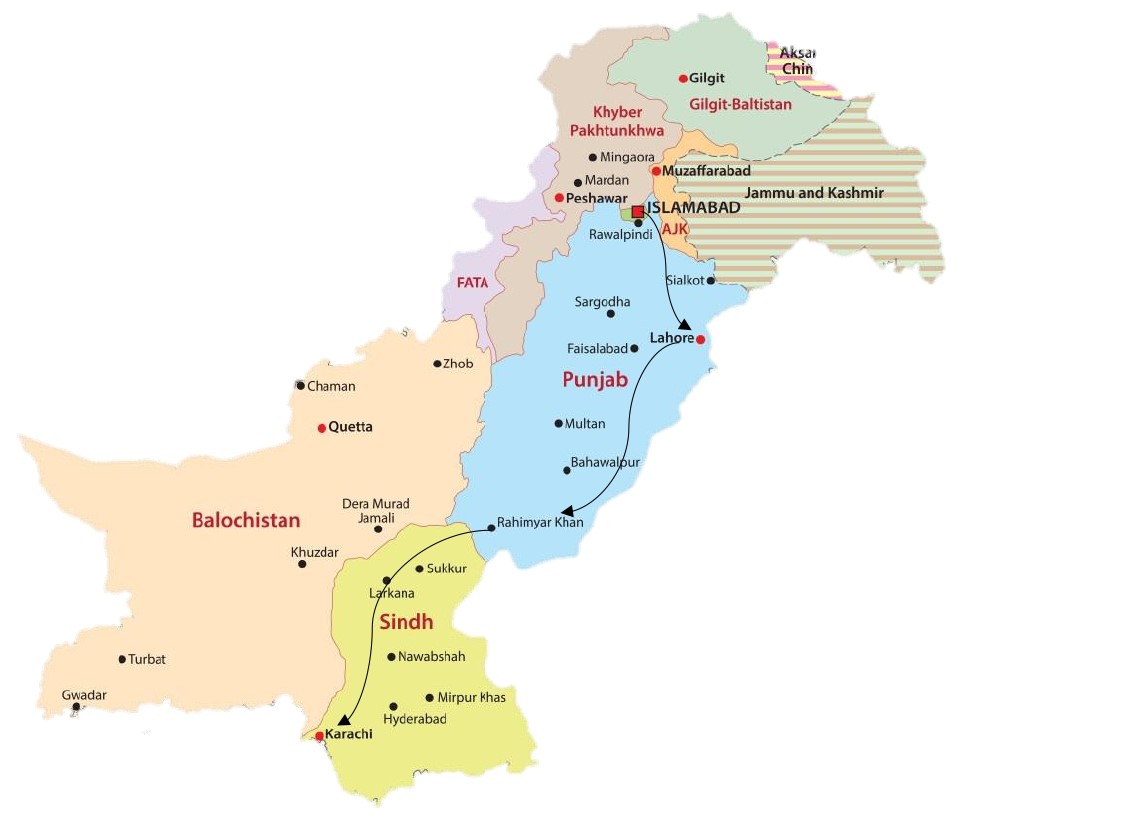

Traveling by road gave me a front-row seat to the evolving infrastructure and local attitudes toward foreign education. From the organized calm of Islamabad to the competitive chaos of Karachi, each city offered distinct insights into the cultural dynamics influencing healthcare simulation adoption.

In Islamabad, the capital’s structured environment created fertile ground for engaging educators in conversations about modern simulation practices. Participants were receptive to international knowledge and eager to modernize their methods, even if simulation as a discipline remained underdeveloped. The openness to change was encouraging, though it underscored the urgent need for targeted professional development.

Shifa Tameer-e-Millat University, Islamabad

In Lahore, the cultural undercurrents were more complex. There was a visible blend of eagerness and hesitation. Some institutional leaders showed indifference, while mid-tier educators were more welcoming. The enduring impact of colonial legacy could be sensed in the hierarchical behaviors, architectural aesthetics, and interpersonal interactions. Simulation was often perceived as an expensive and impractical methodology, and gender dynamics further complicated professional engagement, revealing the critical need for cultural sensitivity in advancing inclusive educational models.

University of Health Sciences, Lahore

When I ventured into interior Punjab and Sindh, the contrast was stark. Distance from provincial centers directly affected the quality and reach of healthcare education. Simulation was largely an unfamiliar concept, with limited understanding of its tools, techniques, and taxonomy. In these regions, cultural traditions were deeply embedded, and as a female educator, navigating patriarchal norms required strategic support. My brothers accompanied me, and their presence—grounded in familial respect—was essential to building trust and acceptance. This highlighted not just the power of family in overcoming societal constraints, but also the potential for simulation to challenge and gradually transform entrenched gender roles in healthcare settings.

Sheikh Zayed Medical College and Hospital, Rahim Yar Khan

Finally, in Karachi, the country’s largest and most fast-paced city, the academic environment was marked by competition and innovation. Simulation was more readily embraced, and gender dynamics were less pronounced. However, this also revealed a growing need for structured simulation training programs to meet the rising expectations of both educators and learners in such an ambitious ecosystem.

Jinnah Sindh Medical University, Karachi

Fazaia Ruth Pfau Medical College (FRPMC), Karachi

What became clear through this journey is that simulation holds tremendous promise as a unifying force across Pakistan’s diverse cultural landscapes. Its ability to democratize learning, enhance patient care, and reduce disparities makes it a critical tool in evolving healthcare education. However, to realize its full potential, there must be intentional collaboration between healthcare institutions, educators, and policymakers. Investing in infrastructure, cultivating local champions, and developing culturally responsive curricula will be key to scaling simulation sustainably.

For a low-resource country like Pakistan, embracing modern teaching methodologies like simulation can be transformative. Byintegrating these tools within culturally respectful frameworks, we can foster a more inclusive, equitable, and effective healthcare education system.

Personally, this journey has been more than just professional exploration—it has been a reconnection with my heritage. It reinforced my belief that simulation is not just about mannequins and metrics; it’s about people, culture, and the shared goal of better healthcare for all. As we move forward, I remain committed to contributing to this evolution, both within Pakistan and across similar low-resource settings globally.